For years, Rockstar Games defined what an open world game was allowed to be.

Grand Theft Auto taught players that freedom could be anarchic using cities designed not just to be explored, but exploited. Chaos was the point, satire was the language, and consequence was optional. Meanwhile, Bully distilled that same philosophy into something smaller and stranger: a schoolyard sandbox governed by social hierarchies, reputation, and quiet cruelty. Both games aged alongside their audiences, growing more self-aware as consoles and console ports changed, more mechanically complex and more culturally fluent with each iteration. These titles didn’t just succeed, they defined childhood eras.

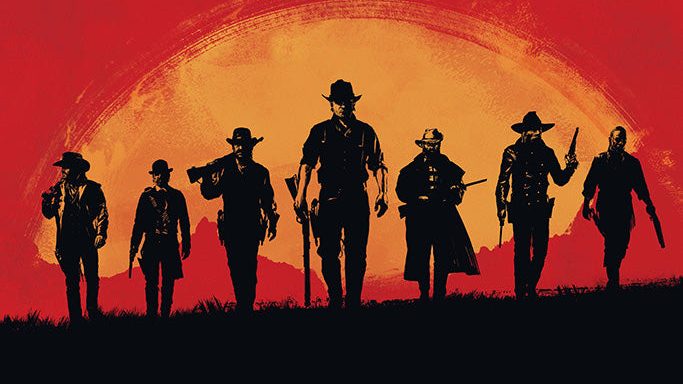

But buried beneath Rockstar’s loudest successes was another property, one treated initially as a side experiment rather than a pillar. A western which proved slower, melancholic, and less interested in satire than in erosion. Where GTA reveled in excess, Red Dead Redemption lingered on decline. And in doing so, it quietly became something else entirely.

By the time Rockstar released Red Dead Redemption 2, the studio had perfected the tools of open-world design: scale, fidelity, systemic interaction, emergent behavior. What they hadn’t yet done—at least not intentionally—was apply those tools in service of restraint. RDR2 is not designed to impress you immediately. It’s designed to wear you down. To slow you. To make time itself feel heavy. From the moment you step into its world, the difference is palpable. The graphics are not just beautiful, they are patient. Weather moves with purpose. Mud clings to boots. Horses tire (and have organs to grow or shrink with the temperature). Guns demand care. Systems do not exist to empower the player, but to anchor them. Every mechanic reinforces the same idea that this world does not revolve around you, and that philosophy extends to its narrative.

Red Dead Redemption 2 is not a story about triumph. It is a story about inevitability. Arthur Morgan is not a power fantasy protagonist, but a man living on borrowed time in a world that no longer has a place for him. The quiet, deliberate, and devastating performances allow the story to breathe. Characters don’t announce their arcs. They reveal them in glances, pauses, and long rides through empty country.

And then there’s the world itself. Years after release, players are still discovering its secrets—ghostly voices drifting through swamps, the unsettling cannibals of the Aberdeen Family Pig Farm, strangers whose stories resolve whether you’re there to see them or not. Nothing begs for attention. Everything waits, and this is what makes RDR2 feel alive in a way few open worlds ever have. It is organic rather than reactive. The game doesn’t perform for you…it continues without you.

The success was immediate and overwhelming. Red Dead Redemption 2 wasn’t just critically acclaimed; it reshaped expectations. It proved that open worlds didn’t need to be louder to be deeper. That immersion could come from friction. That realism, when paired with intention, could be transformative. And players remained entirely devoted to that honeymoon phase until the anticipated launch of Red Dead Online, which stood poised to become a genuine contender alongside GTA Online. The foundation was there, a player base was hungry for more, a world was rich enough to support endless stories, and systems were begging to be expanded and further explored. However, in the wake of such anticipation, Rockstar hesitated. Updates slowed. Communication thinned. Ambition narrowed. Slowly, Red Dead Online was left to be overshadowed by the relentless profitability of GTA Online, until Rockstar stopped speaking about Red Dead altogether.

It was a tragic end, and proof that Rockstar didn’t set out to make the best open-world game of all time. They were refining systems, iterating on legacy, and chasing scale. But in committing fully to atmosphere, consequence, and character, they accidentally created a world that felt too alive to be treated as disposable, a world that stands now as both a pinnacle and a warning. Proof that open worlds can be art and evidence of how easily even the greatest creations can be left behind when they don’t fit a monetization roadmap.

Some worlds are built to be exploited. Others are built to be remembered. Rockstar made both. Yet only one of them was deemed unfit to be kept.

Leave a comment